Long COVID on Creatine

Exploring creatine’s role in energy metabolism and recovery in long COVID (Part 1)

Creatine

Creatine is the most studied supplement on the market. In the world of athletics, it has been a focus for decades—known for improving strength, recovery, and performance. But lately, it’s gaining attention in an unexpected community: people living with long COVID.

Across social media groups and patient forums, many have shared that supplementing with creatine has helped ease symptoms like fatigue, energy crashes, post-exertional malaise (PEM), brain fog, and exercise intolerance. I count myself among them. After struggling with PEM and exercise intolerance during my long COVID journey, adding creatine made a noticeable difference for my symptoms.

For those who are new here, I’ve previously shared the strategies that supported my recovery. There wasn’t one single thing that helped me improve—it was a whole-body approach that I personalized to my condition. For a detailed breakdown, you can explore my five-part Decoding Dysautonomia series here.

Creatine hasn’t been a magic fix, but more like an added layer once the foundational strategies were in place. You can’t supplement your way around the basics; think of this as a next-level support—a potential tool to refine and enhance recovery once the groundwork is solid.

Of course, anecdotes aren’t the same as evidence, but they often point us toward important questions for research. So where does the science currently stand, and what might explain these improvements?

Let’s start with the basics.

How Muscles Make Energy

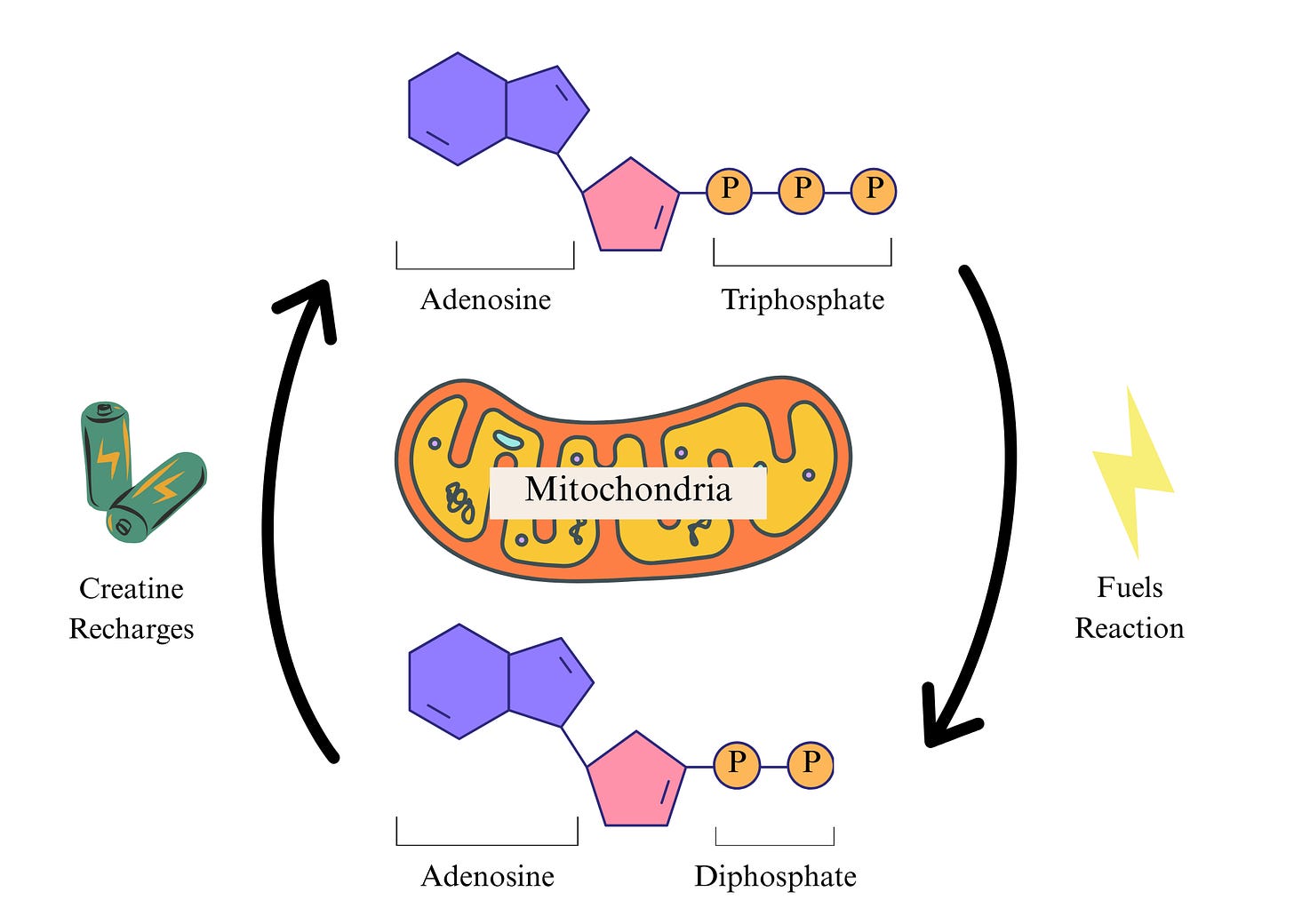

Muscles prefer to use glucose from the food we eat as their main energy source because it can be rapidly converted into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). ATP is the body’s main energy carrying molecule, powering movement in the muscles as well as performing countless cellular functions.

To fully grasp how this process works we need a quick biochemistry lesson. I promise to keep it simple!

First, let’s break down what ATP actually is. The “triphosphate” part of its name means it carries three phosphate groups. When a cell needs energy, ATP releases one of those phosphate groups to power the reaction. Once it loses a phosphate, it becomes adenosine diphosphate (ADP)—with “diphosphate” meaning it now only has two phosphate groups.

You can think of ATP as a fully charged battery, and ADP as the drained battery waiting to be recharged. And this is exactly where creatine comes in.

The Creatine Shuttle

Creatine is a natural compound found in your body and in certain foods like meat and fish. Its main role is to act as a backup energy source for your muscles and brain.

Muscles store it in a special form called phosphocreatine. When ATP gets used up and turns into ADP, phosphocreatine donates its phosphate group to “recharge” ADP back into ATP almost instantly.

Think of it like a fast-charging pack for your drained battery. While mitochondria are busy producing new ATP, creatine helps keep the energy supply stable during short bursts of demand.

Because of this important role, individuals with long COVID are at an energetic disadvantage. A recent nature communications study showed significantly reduced creatine levels in muscle tissue of people with long COVID compared to healthy controls. This suggests that the phosphocreatine “shuttle” system—the process that rapidly regenerates ATP—may be less efficient, making it harder for muscles to quickly restore energy. In practical terms, this could help explain why even small amounts of exertion can trigger fatigue and post-exertional malaise in this population.

For a deeper discussion on long COVID PEM, check out my article here:

Given this potential disruption in energy metabolism, researchers have begun exploring whether restoring creatine levels through supplementation could help support recovery and reduce symptoms like fatigue in people with long COVID.

What the Research Says

This is a very new area of research—as most topics related to long COVID are—so the research on this topic is limited. I have reviewed the current literature related to creatine supplementation and long COVID and summarized a few of those articles here.

Creatine Supplementation in Long COVID Fatigue

A small 2023 study investigated whether creatine supplementation could help individuals experiencing post–COVID-19 fatigue syndrome, a common and debilitating symptom of long COVID. In the study, six participants took 4 grams of creatine monohydrate daily, while a control group took an equivalent amount of inulin (a type of fiber) over a six-month period.

Those in the creatine group reported less general fatigue and greater exercise tolerance, meaning they were able to exercise longer before reaching exhaustion. Muscle tissue analysis also revealed higher creatine levels, suggesting that supplementation helped replenish depleted stores.

While the sample size was small, its findings are promising and lay the groundwork for larger, more definitive studies.

Creatine + Glucose for Enhanced Recovery

Another small but encouraging study explored the effects of creatine combined with glucose in people with long COVID. Over an eight-week period, participants who took 8 g of creatine with 3 g of glucose daily showed increased creatine levels in both muscle and brain tissue and reported notable improvements in fatigue, general malaise, body aches, breathing difficulties, and headaches compared to baseline.

The key takeaway here is that creatine supplementation, especially when paired with glucose, may help ease some of the physical fatigue and malaise associated with long COVID. These findings add to a growing body of evidence suggesting that creatine may be a supportive strategy for restoring depleted energy reserves after viral illness.

Clues from Related Conditions

Emerging evidence suggests that long COVID shares key biological features with other fatigue-related conditions, including chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) and fibromyalgia.

Researchers studying these disorders have found elevated levels of creatinine (a byproduct of creatine metabolism) in urine samples, which were linked to greater fatigue and pain severity. This finding suggests a faster turnover and depletion of the body’s creatine stores.

Because creatine plays a vital role in helping the body recycle energy at the cellular level, its depletion could contribute to the persistent exhaustion seen in post-viral conditions like long COVID.

Supporting this idea, the study found that supplementing with guanidinoacetic acid (GAA)—a compound the body uses to make creatine—helped reduce fatigue in people with fibromyalgia. Taken together, these findings hint that creatine and its precursors may play an important role in restoring energy balance and improving fatigue in post-viral and fatigue-related syndromes.

Future Research

To my knowledge, there are currently no available studies that directly investigates creatine as a potential treatment for the symptom post exertional malaise (PEM) specifically. However, there is a study in the participant recruitment stage from the University of Calgary that plans to research this topic.

In the long COVID world, it takes time for the research to catch up, but I am feeling optimistic about this study. I will keep a close eye on the status and report back when it is published. I am hoping it will add to the growing evidence that creatine could be one piece of the puzzle in addressing post-viral fatigue and long COVID–related PEM.

My Regimen

Now that we have covered some of the research on creatine and its role in energy metabolism in the muscles of healthy individuals as well as the long COVID population, let me share my personal experience with supplementation and what I found to be helpful.

I began taking creatine when I noticed my exercise progress stalled. One of my most frustrating symptoms was extreme soreness after even minimal activity. It often took days, sometimes a full week, to recover from a single workout.

Rebuilding Strength & Endurance

I began my reconditioning journey a little over a year ago, once I had fully recovered from a severe case of rhabdomyolysis. For me, rebuilding started with pacing and gradually reintroducing movement through graded exercise. Everyone’s starting point looks different, but for me, that meant beginning with 10-minute walks around my neighborhood. Over time, those walks stretched to 30 minutes, then an hour, up to a five-mile nature trail. Eventually, I worked my way back up to more intense hikes and even short runs.

I was understandably nervous to jump straight back into strength training at the gym. Instead, I signed up for a few months of barre classes—a low-impact, mostly body-weight form of exercise that helped me transition safely. From there, I slowly reintroduced gym workouts, lowering my usual weights and avoiding overly strenuous eccentric movements.

Now, I’m back in the gym regularly and back on the yoga trapeze—something I once doubted I’d be able to do again. It’s something I have been passionate about since before I developed long COVID, so it feels extra special to enjoy this hobby again. If there’s any interest, I’d love to share more about this practice and how it benefits the body in a future article!

How I Take Creatine

Creatine became a key piece of this journey back to the gym and more intense forms of exercise. Even though I was already focusing on the foundational habits, like prioritizing nutrient timing by fueling adequately before exercise and eating protein within an hour after workouts, I still couldn’t shake the post-exercise soreness. Once I added creatine, things began to shift.

I started with 5 grams of creatine and one scoop of amino acids in a large glass of water daily. I like the Kion brand for both. I drink half the mixture before exercise and the other half after, even on lighter days when I’m just going for a walk. I’m not sponsored by Kion, I just genuinely trust their product quality. For those who struggle with the grainy texture of creatine, I find the flavor from the aminos helps mask it. Personally, I prefer mixing it in with something flavored—whether that’s the aminos, tea, an Olipop, or whatever I have on hand. An additional tip is using a milk frother to help dissolve the powders!

Another excellent option is Thorne, a company known for high manufacturing standards. I have a lot of respect for this company as it has an A rating from Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), which has strict regulations for assessing, evaluating, and monitoring products defined as therapeutic goods. I’ve recommended Thorne to clients, friends, and family in the past and also use their products in my private practice.

If you’d like to try their creatine, you can use my link for 15% off.

Make sure to set up a free account for the discount to apply. To do this click “sign in” then “start here!”

Choosing a Quality Supplement

Regardless where you choose to buy your creatine from, here are a few things to keep in mind. First, look for a brand that 3rd party tests their products so you know what is actually in the product. One certification that does this is NSF Certified for Sport, the “gold standard” for quality, purity, and safety in dietary supplements.

It’s also helpful to look for certifications like Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP), which ensure the product was produced in a facility following high-quality manufacturing standards.

The supplement industry is not regulated, so unfortunately it is up to the consumer to make educated decisions when purchasing.

Types of Creatine

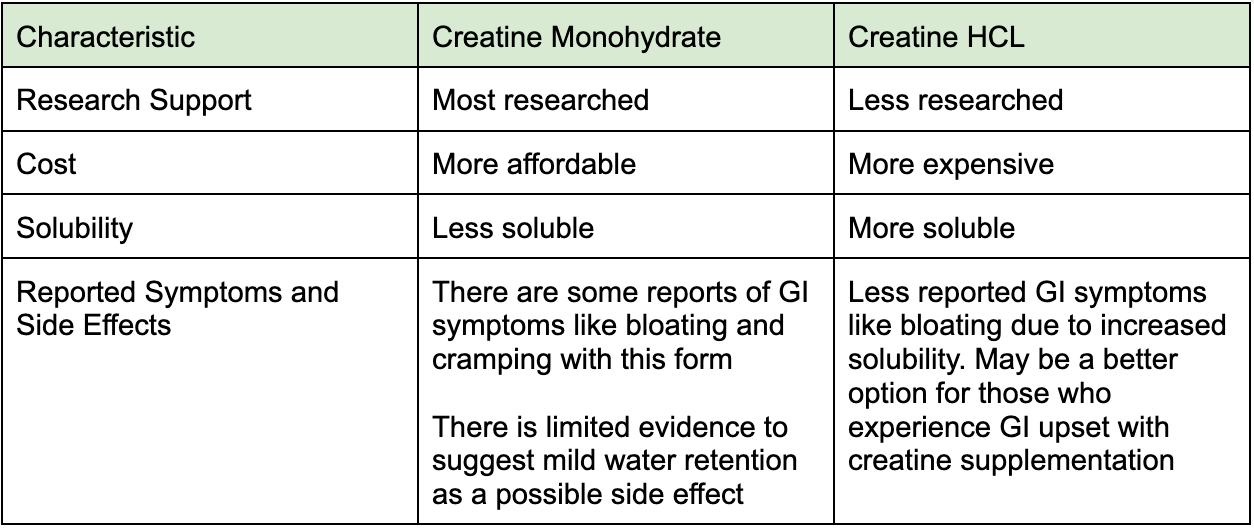

Once you decide if creatine is right for you and where to purchase it from, it is also important to know which type of creatine best fits your needs. There are two main forms of creatine to choose from: creatine monohydrate and creatine HCL. Let’s break down their differences:

Medical Disclaimer

While creatine’s safety profile in the literature is well-established, that doesn’t mean it’s right for everyone.

This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as professional medical advice. Always consult your healthcare provider before taking creatine, combining it with any medication, or before making changes to your treatment or lifestyle.

Dosage Guidelines

Some people start with what’s called a “loading phase,” where they take larger amounts of creatine (typically 15–20 g per day, split into several doses) for a few days to quickly saturate the muscles. After that, they transition to the standard maintenance dose of 3–5 g per day.

I personally skipped the loading phase. I tend to take a more conservative approach when starting new supplements. Because higher doses may cause mild digestive symptoms, like bloating or cramping, I opted for the gradual route of taking 5 g per day from the start. It takes a bit longer for the muscles to become fully saturated, but it’s easier on the digestive system and still achieves the same end result over time.

Staying Hydrated on Creatine

Creatine draws water into the muscle cells, so hydration is important. It’s helpful to listen to your body’s thirst cues and use urine color as a guide. Pale yellow typically indicates good hydration.

Potential Side Effects

Lastly, while creatine is generally well tolerated, a few side effects have been reported. The most common one is mild gastrointestinal upset. While the literature does not show consistent evidence of creatine causing GI symptoms, it has been reported anecdotally by users. It often resolves with a few adjustments:

🛑Ensuring the powder is fully dissolved before drinking

🥤Taking it with food and adequate water

🐢Gradually increase your dose and avoid the “loading phase”

For those who continue to experience discomfort, creatine HCl may be a better-tolerated option than the traditional monohydrate form.

Wrapping Up

The research on the potential benefits of creatine for long COVID patients is still limited and future studies are needed to confidently say it is an effective treatment strategy for this complex chronic condition. Based on patient self reports and the available literature, it seems there is growing preliminary evidence that this supplement may reduce muscular and fatigue-related symptoms for long COVID management.

Based on the extensive research on creatine supplementation and its safety, I decided to give it a try. I found it to be helpful in my experience for reducing fatigue, PEM, and exercise intolerance. My goal in sharing this article is to provide a patient perspective guided by the available science as to why this may be effective for some people in the long COVID community.

Stay tuned for the next article: “Your Brain on Creatine” — where we will be diving into creatine’s effect on the brain for the general population as well as the emerging evidence showing improvements in cognitive symptoms in long COVID patients.

Buy Me a Coffee ☕ (Decaf, of course)

My goal is to keep my work free and accessible to the chronic illness community. Living with chronic conditions can be financially draining, and for many of us who are partially or fully disabled, accessing support and care can feel out of reach.

I have recently enabled the paid subscriber feature, but will never paywall my work. This is simply for anyone who has the means to contribute and would like to support financially. Or if you’ve found this article to be helpful, I’ve set up a Buy Me a Coffee page—a virtual tip jar where you can make a small donation if you’d like.

Your support helps make it possible for me to continue pouring time, research, and lived experience into creating these resources.

Whether you’re able to contribute or not, I’m so grateful you’re here. Thank you for being part of this community. 💛